Joseph Plateau created the first device to make pictures move in 1832. Eleven years later he went completely blind. He continued conducting scientific research for another 40 years, making his most important discoveries after losing his sight.

The Belgian physicist died in Ghent on 15 September 1883 at age 81. His phenakistiscope established the foundation for cinema. His work on soap bubbles, done without vision, gave us mathematical principles still used in architecture and physics today.

Table of Contents

The Dangerous Experiment

In 1829, Plateau stared directly at the midday sun for 25 seconds. The 28-year-old physicist wanted precise measurements of how long light impressions lasted on the retina for his doctoral thesis at the University of Liège.

Pain hit immediately. For days afterwards he struggled with severe discomfort and distorted vision. The symptoms eventually faded, but he had permanently damaged his eyes. He earned his doctorate in physical and mathematical sciences on 3 June 1829, having compromised his eyesight during the research itself.

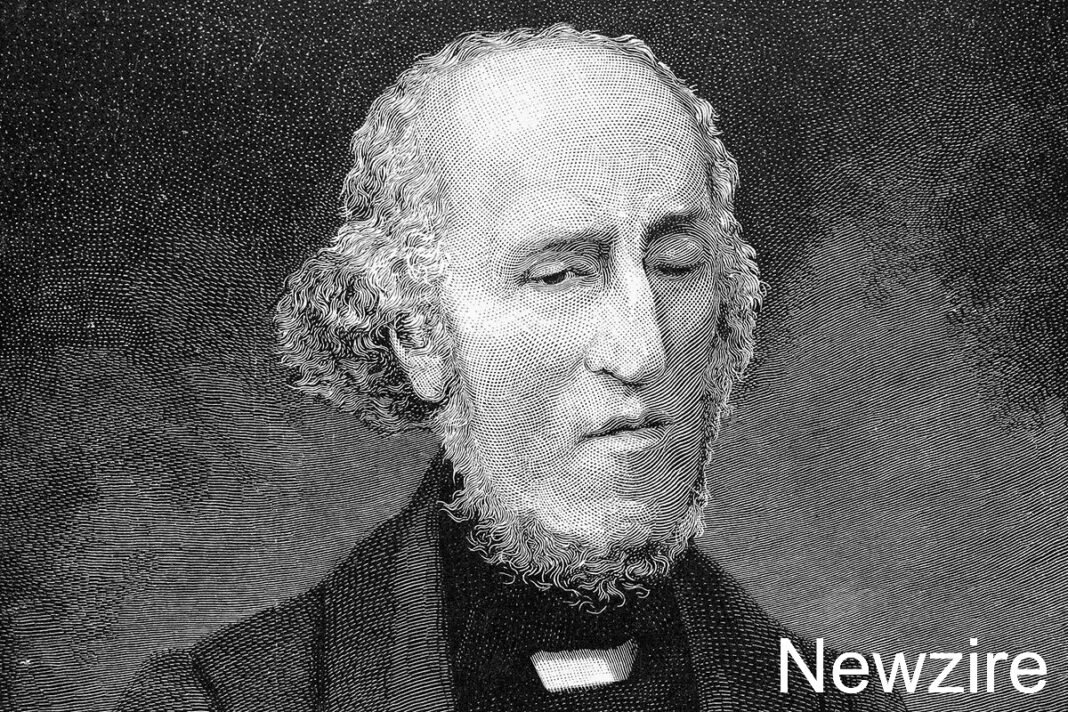

Joseph Antoine Ferdinand Plateau had been born in Brussels on 14 October 1801 to an artistic family. His father Antoine painted flowers professionally in Tournai. Both parents died when he was 14, and his uncle, lawyer M. Thirion, took him in. Despite initial training at the Academy of Fine Arts, physics experiments he witnessed at primary school captured his interest. He studied mathematics at the Athenaeum in Brussels from 1817, where Adolphe Quetelet recognised his abilities and became a mentor.

Spinning Discs and Moving Images

Three years after damaging his eyes, Plateau invented the device that would make him famous.

The phenakistiscope used two cardboard discs mounted on a single axle. One disc had evenly spaced viewing slots cut around its edge. The other showed sequential drawings of a figure in different stages of motion: a dancer mid-pirouette, a horse at full gallop, an acrobat tumbling.

Users spun both discs whilst holding them up to a mirror. At the correct rotational speed, the separate drawings merged into smooth animation. The phenakistiscope became the first device to create the illusion of moving pictures.

Austrian mathematician Simon Stampfer invented an identical device during the same month of December 1832. Both men had read Peter Mark Roget’s 1824 paper describing optical illusions created when viewing rotating wheels through vertical slits. They invented the same device because the science was ready.

Belgian painter Jean-Baptiste Madou, who later married into Quetelet’s family, designed the artistic content for Plateau’s discs. Madou created intricate sequences: monks walking through cloisters, figures blowing coals into flames. Plateau supplied the physics and mechanical design.

London publisher Ackermann & Co released the invention in July 1833, calling it the Phantasmascope. French manufacturers adopted the name Phénakisticope, derived from Greek words meaning “deceptive eye.” Toymakers across Europe quickly produced their own versions. The device became a popular parlour entertainment.

By 1827, Plateau had secured a mathematics teaching position at the Athenaeum in Brussels. His research on visual perception attracted notice. In 1835, Ghent University appointed him extraordinary professor of physics based on his groundbreaking work on how the eye processes light and motion.

From Observation to Darkness

In 1840, while Plateau still had his vision, a servant accidentally spilled oil into a container of water and alcohol. Plateau observed the oil droplets forming perfect spheres suspended in the mixture. The phenomenon interested him enough to begin preliminary experiments.

A year later, in 1841, his vision started deteriorating. Blurred sight at first, then black spots floating across his field of view. He consulted specialists in Brussels, but nobody could halt the progression.

The deterioration accelerated through 1842 and into 1843. By late 1843, aged 42, he had lost all sight in both eyes. He blamed his 1829 sun experiment. Modern medical analysis suggests he suffered from chronic uveitis, an inflammatory eye condition unrelated to sun damage. Plateau never learned this. He believed until his death that scientific curiosity had cost him his vision.

Ghent University promoted him to full professor on 29 June 1844, just months after he went blind. He continued working with his family’s help.

Seeing Through Family

His wife Augustine Thérèse Fanny Clavareau, whom he had married on 27 August 1840, became essential to his continued research. For the next four decades she described experimental results he could no longer observe directly.

Their son Félix handled the physical apparatus and conducted experiments under his father’s verbal direction. Félix later became a professor of zoology at Ghent himself. Daughter Alice married physicist Gustave Van der Mensbrugghe in 1871, and Van der Mensbrugghe took on the role of primary scientific collaborator and note-taker. He would eventually write the first biography of his blind father-in-law.

British scientist Michael Faraday, who had corresponded with Plateau about optical devices throughout the 1830s, later observed that although Plateau had been “plunged in the darkness of a sad profound night,” his mental faculties had “become more intensive than ever” and led to his “most brilliant discoveries.”

Research Without Sight

Between 1843 and 1868, Plateau developed more than 80 experimental apparatus designs for studying soap films, all whilst unable to see any of the results.

The method required precision. His wife, son, or son-in-law would dip wire frames of various shapes into solutions of soapy water and glycerine. They would then describe in exact detail what surfaces formed when the frames were withdrawn: where films met, at what angles, how curves connected.

Plateau listened to these descriptions and worked out the underlying mathematical principles. Three soap films always meet along a curve at precisely 120-degree angles. Four such curves meet at vertices forming angles of approximately 109 degrees. Every surface maintains constant mean curvature at every point.

These observations became known as Plateau’s Laws, fundamental principles governing minimal surfaces and soap bubble behaviour. A blind physicist deriving complex geometry from verbal descriptions provided by family members who were not scientists themselves.

In 1873, Plateau published Statique expérimentale et théorique des liquides soumis aux seules forces moléculaires across two volumes totalling nearly 1,000 pages. The work summarised his decades of research on liquids and molecular forces. Every word had been dictated.

American mathematician Jean Taylor proved his experimental observations mathematically in the 1970s, more than 90 years after Plateau’s death. She demonstrated that his laws were necessary consequences of energy minimisation in physical systems. No other surface configurations were possible. His dictated observations, derived from second-hand descriptions, had been correct.

German architect Frei Otto applied Plateau’s minimal surface principles when designing the West German pavilion for the 1967 Montreal Expo. Computer graphics programmers today use his laws to simulate realistic soap bubbles. Mathematicians continue investigating problems he first identified whilst blind.

Honours and Final Years

Belgium recognised his contributions throughout his career. The Royal Belgium Academy of Science elected him a corresponding member in 1834 and promoted him to full membership in 1836. He received the Prix Quinquennal for Mathematics and Physics twice, in 1854 and 1869, for work completed during the previous five-year periods.

King Leopold I made him Knight of the Order of Leopold on 13 December 1841, just as his blindness was beginning. He was promoted to Officer in 1859 and Commander in 1872. The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences elected him a foreign member that same year.

Scholars who visited his Ghent home described a man with sharp wit whose memory had grown stronger rather than weaker with age. He hosted discussions about physics and mathematics, engaging fully in scientific debates despite his blindness.

Plateau retired from Ghent University in 1872 at age 70 but continued his research at home with family assistance. He died there on 15 September 1883.

The Cinema Connection

On 14 October 2019, Google commemorated what would have been Plateau’s 218th birthday with an animated Doodle created by Olivia Huynh. The animation featured spinning discs echoing the phenakistiscope design, making it the first Google Doodle to display different artwork across desktop, mobile, and app platforms.

The Belgian film industry had honoured him decades earlier. From 1985 to 2006, the Joseph Plateau Award recognised achievements in Belgian cinema. The trophy itself was shaped like a phenakistiscope. Streets in Brussels and Ghent bear his name. Ghent University named Campus Plateau after their most famous blind professor.

The phenakistiscope’s commercial success lasted only two years. William George Horner invented the zoetrope in 1834, which eliminated the need for a mirror and allowed multiple viewers simultaneously. That technology evolved into the kinetoscope, then the cinematograph, launching the film industry.

Yet the core principle Plateau discovered in 1832 underlies all moving image technology. Sequential images presented rapidly enough create the perception of continuous motion through persistence of vision. Modern cinema, television, and digital video all stem from his spinning cardboard discs.

The Legacy of Dictated Discovery

Joseph Plateau damaged his vision pursuing knowledge about how we see. His most significant scientific contributions came during 40 years when he could see nothing.

His wife described soap film surfaces forming on wire frames. His son manipulated experimental apparatus according to verbal instructions. His son-in-law recorded observations and calculations. A blind physicist sat in darkness, reconstructing the behaviour of minimal surfaces from descriptions alone, discovering mathematical laws that architects and physicists still apply nearly 150 years after his death.

The phenakistiscope gave us the foundation for cinema. His blind research gave us Plateau’s Laws. Both achievements required the same quality: an ability to perceive patterns others missed, whether in spinning images or in dictated descriptions of soap bubbles he would never see.