On November 14, 1698, Henry Winstanley climbed into a wooden lantern room nine miles offshore and lit 60 tallow candles. His lighthouse was the world’s first in open ocean, and it turned England’s deadliest shipping lane into its safest.

Before that Tuesday evening, the Eddystone Reef claimed roughly 50 vessels every year. During the five years his tower operated, the wreck count dropped to zero.

Table of Contents

The Eddystone Reef

The Eddystone Reef consisted of 23 rust-red rocks nine miles southwest of Plymouth. Sharp Precambrian gneiss blocked the main Atlantic approach to Plymouth Sound. At high tide, the entire reef disappeared beneath the surface, and in darkness, fog, or storms it became invisible.

Mariners called it the dreaded Eddystone. Vicious eddy currents swirled around the rocks and created unpredictable water movements even on calm days. Ships bound for Plymouth Sound had to risk the direct route through the reef or add days to their voyage along the French coast.

Most took the direct route, and by the 1690s over a thousand ships wrecked there. Losses in cargo, vessels, and lives grew steadily.

In 1692, Trinity House petitioned King William III for permission to build a lighthouse, documenting constant losses of ships and crews, but the petition failed. Nobody could work out how to build a permanent structure on submerged rocks exposed to Atlantic storms.

Henry Winstanley had personal reasons to try. In 1695, two merchant ships he invested in broke apart on the Eddystone: the Snowdrop and the Constant went down with their crews and cargo, costing him a substantial sum.

According to contemporary accounts, Winstanley learned about the wrecks in a London pub, left immediately for Plymouth, and demanded to know why the reef remained unmarked. Authorities told him the location was too dangerous, but he said he’d build the lighthouse himself.

Trinity House spent years trying to find someone willing to attempt the project, so they granted him a patent.

Three Years of Construction

Work began in summer 1696. Getting to the reef took six hours of sailing and rowing from Plymouth, with another six hours for the return journey, and the crew could only land at low tide during a window of roughly three and a half hours. On bad days, which were frequent, waves made landing impossible.

The first year: Winstanley’s team drilled 12 holes into the ancient gneiss bedrock using hammers and iron spikes, gouging away grain by grain. When those holes were ready, they inserted iron stanchions 13 feet long and 3.5 inches thick and set them with molten lead.

Those stanchions anchored the tower. Other builders later copied the construction methods Winstanley developed on the Eddystone.

War between England and France complicated the second year. On June 25, 1697, a French privateer destroyed the partially built stone base, kidnapped Winstanley, and took him to prison.

King Louis XIV learned of the capture and ordered Winstanley’s immediate release, reportedly saying: “France is at war with England, not with humanity.” The French monarch understood the lighthouse would save his sailors as much as English ones.

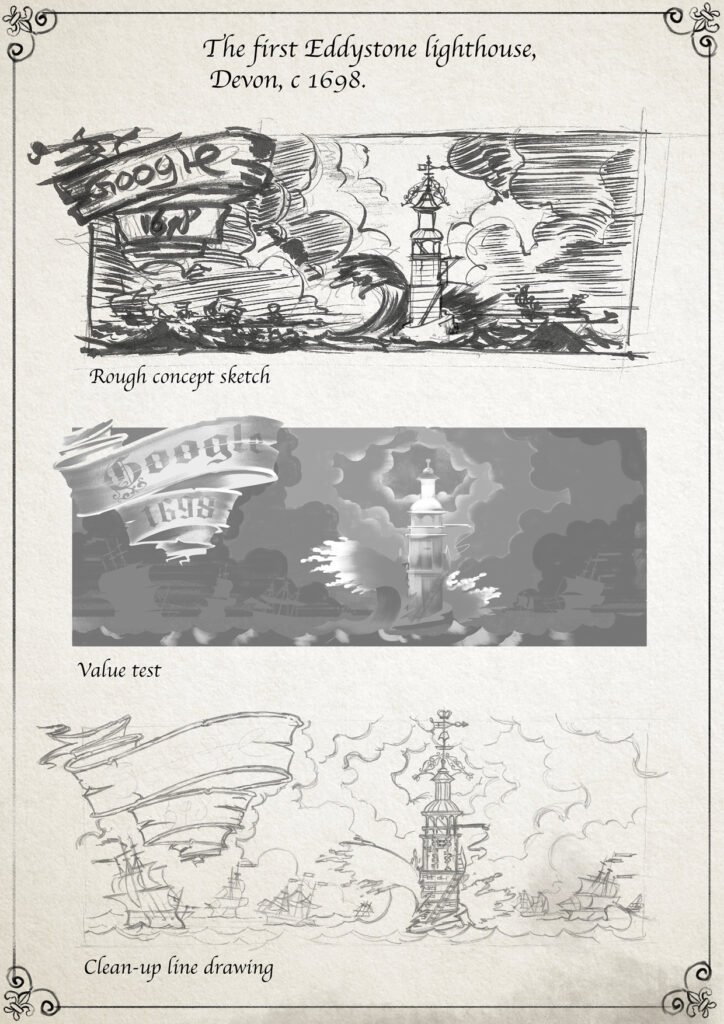

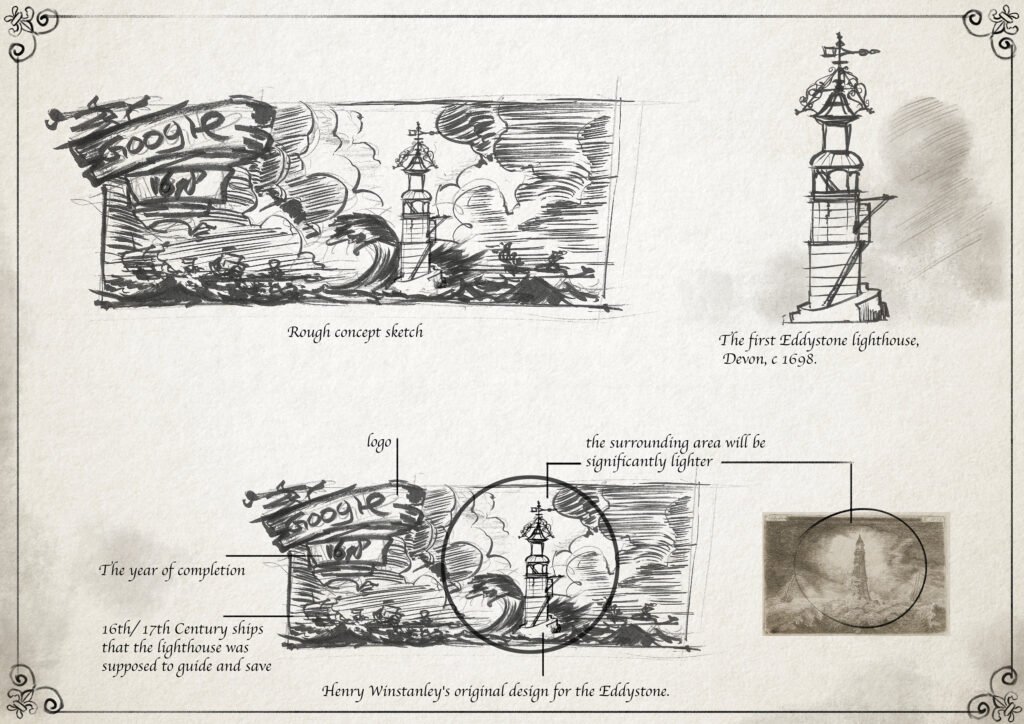

Winstanley returned to Plymouth and resumed construction with a Royal Navy warship on guard. By autumn 1698, the octagonal wooden tower stood 80 feet above the rocks with a lantern room that had eight windows, each containing 36 individual glass panes.

Winstanley previously ran Winstanley’s Waterworks near Hyde Park. That popular London attraction featured mechanical devices and perpetual fountains. His lighthouse included elaborate galleries and decorative ironwork. Critics compared the structure to a Chinese pagoda while engineers questioned whether something so ornate could survive winter storms, but Winstanley ignored both.

The First Lighting

At nightfall on November 14, 1698, Winstanley lit the chandelier of 60 candles while a large hanging lamp provided additional light, and the beam was visible for 14 miles.

In Plymouth, sailors spotted the light and word spread through the waterfront taverns and dockyards as ships’ bells rang out across the port. Mariners finally had a warning light for the Eddystone, and celebrations lasted well into the night.

Winstanley couldn’t join the celebrations because weather deteriorated immediately after he lit the candles. Waves crashed over the tower and wind increased steadily. For five weeks, he and his construction crew remained trapped on that rock while supply boats couldn’t reach them and their food supplies dwindled until conditions finally calmed enough for rescue.

The first winter exposed serious problems: waves regularly covered the entire structure and blocked the light, while the constant battering made the tower shake and cement eroded faster than Winstanley expected.

By spring 1699, he knew he needed to rebuild. He expanded the base to 20 feet high and 24 feet in diameter, added more iron hoops around the pillar, and changed the octagonal design into a dodecagonal structure with extra stonework. The rebuilt version was completed by summer 1699 and was considerably stronger than the original.

Zero Wrecks

Shipping through the western Channel shifted after 1698. Ships that previously avoided the direct approach to Plymouth now sailed straight for the port. Vessels departing for Atlantic crossings used the Eddystone light as their final navigation point before open water.

Not a single ship hit the Eddystone Rocks between 1698 and 1703. Insurance underwriters in London adjusted their rates for vessels on the Plymouth route as the risk dropped significantly, and shipping companies scheduled more frequent departures now that the approach was marked.

Trinity House collected tolls at one penny per ton from passing vessels, generating revenue of £4,721 between 1698 and 1703, though construction and five years of maintenance cost £7,814. Despite the financial shortfall, Winstanley had built a working offshore lighthouse that generated revenue.

Shipping logs from that period recorded the relief that crews felt when the Eddystone light came into view. Sailors who feared the reef for their entire careers now used the light as a safe navigation marker.

Winstanley’s confidence in his structure grew, and he declared his wish to be in the lighthouse during “the greatest storm that ever was” to demonstrate the tower’s strength.

The Great Storm

On November 27, 1703, Winstanley was conducting maintenance on the lighthouse when the Great Storm struck with wind speeds exceeding 100 miles per hour, battering the southwest coast from midnight until well past dawn in one of the worst storms ever recorded in British history.

When morning broke on November 28, Plymouth residents looked towards the Eddystone and saw bare rock where the lighthouse had stood. No trace remained except the 12 iron stanchions still grouted into the bedrock where Winstanley’s team set them in 1696. Winstanley and five lighthouse keepers perished, and no one recovered any bodies.

A few days later, the tobacco ship Winchelsea wrecked on the Eddystone Rocks as the crew returning from Virginia expected to see the lighthouse and sailed straight into the reef, losing all hands.

Winstanley’s widow, Elizabeth, applied to Queen Anne for compensation and received £200 in 1707, with annual payments of £100 beginning in 1708 as formal recognition of her husband’s contribution to maritime safety.

Three More Lighthouses

Winstanley’s tower was destroyed, but lighthouse construction on the Eddystone continued.

John Rudyerd built the second lighthouse in 1709, a smooth conical wooden tower that stood for 47 years before burning down in 1755. John Smeaton constructed the third in 1759 using techniques based on Winstanley’s iron stanchions and dovetailed joints, and his innovations in hydraulic concrete and interlocking stone blocks changed lighthouse engineering.

James Douglass built the fourth lighthouse between 1878 and 1882, a granite tower that still operates today after Trinity House automated it in 1982 as the first offshore lighthouse converted to automatic operation. Modern equipment replaced candles with electric lamps and solar panels.

Winstanley’s work on the Eddystone proved offshore lighthouses could be built, and future builders used his construction methods. The Royal Museums Greenwich archives document how these techniques spread through British maritime engineering.

The current Eddystone Lighthouse guides ships through waters that once claimed 50 vessels annually. When mariners approach Plymouth Sound today, they see a light that first shone on November 14, 1698, when Henry Winstanley lit 60 candles in a wooden tower. He never left it alive, but every offshore lighthouse built since used techniques he developed.